Foraging for edible ‘weeds’ – yes really!

I recently met up with an enthusiastic group of potential foragers on a cold wintry morning in Tempe, a suburb just south of the centre of Sydney. We walked along the bushy park that lines the Cooks River and winds its way to Marrickville in Sydney. It was a fine day, overcast but chilly in that wintry way. There were 16 of us plus our guide Diego Bonetto, better known as The Weedy One.

One man’s weeds are another man’s dinner!

Carrying a small basket, Diego started our tour by bending down and digging out a dandelion, complete with long tap root and tooth-shaped leaves. His implement was his pen knife which he considers the best weeding tool. Closely followed by a screwdriver! During the next three hours, he amazed me by finding mysteriously seasonal wild treats such as Lomandra, Pigface, African olives, cudweed, Warrigal greens, rambling dock and mallow.

I have been interested in the nutritional value of edible weeds for some time ever since I researched their history for an interview for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC similar to the BBC in the UK). I always appreciated their medicinal value. Read it here.

The perfect guide

Diego was a perfect guide, being an expert, professional forager for over 20 years and a well-known personality. He regularly runs foraging walks and talks at workshops on harvesting your own greens. Find out more at his website www.diegobonetto.com.

His philosophy is that humans have always foraged but our current generations have lost the skill of finding where the wild and unwanted things grow. Many of our grandparents had it and foraged for mulberries, blackberries, nasturtium leaves, purslane, wild fennel, wild figs, watercress, samphire and stinging nettle but now, with increasing urbanisation and the rise of reliance on supermarkets, this knowledge has largely disappeared. Fortunately, it’s undergoing a revival now - and I was with him to learn on the go.

Foraging is a way of life

Many European cultures practice and enjoy foraging for both food and medicine. Here are 3 simple examples:

Many European cultures practice and enjoy foraging for both food and medicine. Here are 3 simple examples:

- My parents hailed from Poland where they regularly ventured into the forest after rain to pick the wild mushrooms that would pop up (note: don’t attempt this yourself unless you are absolutely sure you’re picking the right mushroom as there are deaths every year from people eating the wrong ones!).

- When I posted a couple of pics of this excursion on Instagram, one of my followers replied that her grandmother came from Greece where the women in each village picked ‘horta’ or wild greens each spring. And how angry her grandmother would get at them being called ‘weeds’ and dismissed as ‘inedible’.

-

Picking fresh fronds of wild fennel Foeniculum vulgare is well known - any time you spot those thin feathery bushes around an old railway track or vacant block, you’re in luck with something wonderfully flavoursome with a strong liquorice aroma but make sure they haven’t been sprayed by your local council. These days most sprays have a coloured dye in them so you can tell at a glance.

Our foraging tour kicked off with Diego digging up that fresh dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). He then showed us how to spot dandelion from its lookalikes and how to pick the fresh young leaves for a salad. According to him, dandelion is the ‘king of detox weeds’ and a well-documented detoxification herb with a long history of use by many different cultures.

Meeting Lomandra

We strolled down the park following the river alongside masses of planted mat rush known as Lomandra, with its long tough reed-like leaves which the Aborigines would dig to munch on. You would recognise it immediately, as it’s planted everywhere today on traffic islands and sides, thanks to its hardiness and drought tolerance.

I tried a bite of the beige starchy base of the strappy leaves and found it tasted vaguely like green peas. Hard work to get a feed! Best left for basket making and weaving thanks to its tough fibres, methinks.

Meeting Pigface

Diego also cut an end piece of Pigface, a juicy succulent with a pretty pink flower that is a common ground cover. Official name is Carpobrotus spp.

Interestingly one of our group was an older Australian woman Ann and she recognised most of the plants, having foraged as a kid when ‘playing’ outdoors or watching her mother pick something edible outdoors.

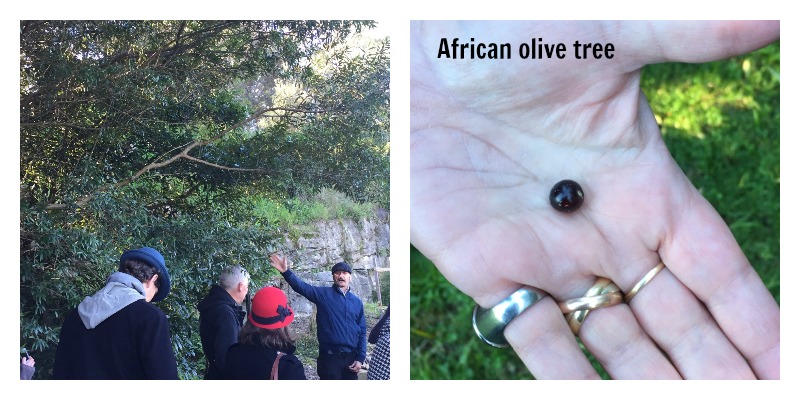

Meeting African olives

Diego pointed out a tall African olive tree Olea europea sub spp cuspidate that somehow was managing to grow in the crevice of a sandstone outcrop in the park. It looked strong and attractive with its longish silver glossy leaves. It produced a black olive fruit that had a large pip with not much flesh. I know, I tried it. Rather bitter in taste too, as regular fresh olives are too.

Diego pointed out a tall African olive tree Olea europea sub spp cuspidate that somehow was managing to grow in the crevice of a sandstone outcrop in the park. It looked strong and attractive with its longish silver glossy leaves. It produced a black olive fruit that had a large pip with not much flesh. I know, I tried it. Rather bitter in taste too, as regular fresh olives are too.

Diego told us that this tree is being actively cut down in many parts of Australia as it’s now regarded as noxious. It is very hardy and flourishes in places where native trees can’t so I can’t see why we couldn’t cultivate it for its crop.

Meeting Warrigal greens

We spotted a few Warrigal greens (Tetragonia tetragonoides) which would have saved the early British settlers from scurvy (deficiency of vitamin C). A nice green veg but not much taste IMHO. Best to pick the younger leaves and use as a substitute for English spinach.

Meeting Farmer’s Friend

We tasted the young yellowish flower head of Farmer’s Friend (Bidens pilosa), which had a pleasant tang to it. I had no idea it was edible when young. If we all ate it before it grows into those awful stick-onto-everything long brown seeds, we’ll be ridding the outdoors of something definitely unwanted. I still pick them off my jeans when out in the bush.

Other edibles

Diego also dug out and showed us cudweed, rambling dock, red flowering mallow and scurvy weed. He concluded by spreading out a collection of the 14 items he’d picked that morning and identifying them again for us. A marvellous reminder, as was the small book we each received with pictures of the most common edibles on his walks.

Diego’s 3 rules of foraging

I loved Diego’s three Golden Rules for foraging which are:

- Know your local area, so you know what grows where each year (whether they’ve been sprayed or if it’s likely that a dog has peed on them e.g. near a corner, growing low). Make a mental note to return and collect next year.

- Be quite sure you know what you’re picking. If you’re unsure, don’t eat it.

- Be kind. Leave some for the next season or for someone else - don’t harvest the whole lot. My mother used to say this when picking mushrooms i.e. trim off the top fruiting body gently and leave the underground mycelium undisturbed for next time.

The bottom line

I’m a happy convert. With their fresh and free flavour, edible weeds can make a delicious addition to your diet. They are definitely not unwanted nor wild. Many edible weeds are actually higher in important vitamins (beta-carotene), minerals (potassium) and phyto-nutrients (polyphenols) than cultivated vegetables which have been bred for less bitterness, greater yield, ease of transport and bigger leaves – not nutrition.

Want to know more?

- Find out more info about upcoming walks from Diego at www.diegobonetto.com. Follow Diego on Instagram @theweedyone and on Twitter @theweedone. Or on Facebook as Wild Stories.

- The Wondrous World of Weeds At Our Doorstep plus CD by Pat Collins.

- The Weed Forager’s Handbook: A Guide to Edible and Medicinal Weeds in Australia (Hyland House, 2012) by Adam Grubb and Annie Raser-Rowland.