- Home

- Blog

- Carbs, Sugars and Fibres

- High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) - 10 things I’ve learned about it

High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) - 10 things I’ve learned about it

Written by Catherine Saxelby

on Wednesday, 02 September 2015.

Tagged: carbs, healthy eating, healthy lifestyle, nutrition, sugar

High fructose corn syrup, or HFCS, is a controversial ingredient with a nasty reputation. On the one hand, shoppers avoid it in the belief that it’s somehow ‘dangerous’. Many are of the opinion that since it replaced sugar over 40 years ago, it has contributed to the huge rise in obesity, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. In the opposing corner, manufacturers say it’s no different to sugar and that it’s not the culprit. Here’s what I discovered when I started researching into its health aspects.

What is HFCS?

High fructose corn syrup (also called iso-glucose and glucose-fructose) is a sugar syrup. Like honey and maple syrup, it contains around 24 per cent water.

The rest is fructose and glucose (dextrose) – the water just makes the fructose and glucose into a syrup instead of a solid. It’s been plagued by controversy about whether it’s really evil or not. Let’s take a look…

1. I have never seen or bought HFCS

I know it looks like a colourless or pale yellow syrup but I’ve never seen a jar or bottle at any supermarket in Australia. When I Google “Buy HFCS”, I can see that it comes in huge drums with a minimum order of 20 tons from China for US$480-750 a ton. Really it’s an industrial sweetener, available to the food industry.

2. HFCS is NOT fructose

Don’t confuse HFCS with pure fructose, they’re two different things. Despite its name, HFCS is NOT high in fructose. Originally the name was simply to distinguish it from ordinary, glucose-containing corn syrup.

Remember that fructose on its own is a natural, simple sugar that's found in fruit, particularly dried fruits like sultanas and dates, as well as honey, and agave. It has a low GI of 23 which was once thought an advantage and useful for people with diabetes as it doesn’t call for insulin for its metabolism .

Fructose is 1.7 times sweeter than sucrose, despite having the exact same content of kilojoules/Calories. So theoretically, you could use about 60 per cent less fructose than sucrose to get the same sweetness.

HFCS-55, the commonest syrup, is a mix of 55 per cent fructose and 45 per cent glucose with the rest being water. According to the book The Ultimate Guide to Sugars and Sweeteners, no manufacturer has yet published their GI figure but they estimate it to be 56. Sugar has a GI of 65. So they’re similar

3. HFCS is NOT corn syrup

Common corn syrup is made from the same starter grain as HFCS but is almost 100 per cent glucose, while HFCS has had half of its glucose converted into fructose by enzymes. Ordinary corn syrup has been around since the 1920s and I can buy it under the brand name Karo in a light or dark version. Like maple syrup or agave, it still adds a syrupy sweetness to pancakes, waffles and French toast . Corn syrup is a refined sweetener so should be consumed in moderation. On special occasions, say in that famous pecan pie recipe for your American friends once a year.

4. HFCS is a cheap way to sweeten fizzy drinks

The food industry loves HFCS. Why? HFCS is less expensive and more readily available then ordinary sugar because it’s made from an abundant crop (corn) which has enjoyed extensive government subsidies and so has remained immune from the price and availability extremes of cane sugar.

The food industry loves HFCS. Why? HFCS is less expensive and more readily available then ordinary sugar because it’s made from an abundant crop (corn) which has enjoyed extensive government subsidies and so has remained immune from the price and availability extremes of cane sugar.

What’s more, because it’s a mix of fructose and glucose, HFCS is sweeter than ordinary sugar allowing beverage and other sweet product manufacturers to use less sugar without reducing sweetness.

Bottom line – it saves them money, lots of it!

5. Easier to handle

HFCS comes as a liquid which means it can be pumped from delivery vehicles to mixing tanks, requiring only simple dilution before use. Much easier then transporting bags of solid sugar crystals and then waiting for them to dissolve. It is also stable in acidic foods and beverages. In contrast, sugar in an acidic cola drink will gradually split (invert) from sucrose into its component sugars, glucose and fructose.

These reasons make HFCS an attractive alternative to sugar and have driven its spectacular acceptance by the food industry.

6. HFCS is highly processed and NOT a whole food

Manufacture of HFCS only became possible after the 1960s when industrial production methods of enzyme usage were developed and made scalable. The corn starch is wet-milled from maize and converted, by a series of steps, into glucose-rich corn syrups. These are then transformed into fructose syrups by enzymes e.g. isomerase, and then refined. The fructose syrups are blended with the glucose syrups to make variety of commercial syrups.

Manufacture of HFCS only became possible after the 1960s when industrial production methods of enzyme usage were developed and made scalable. The corn starch is wet-milled from maize and converted, by a series of steps, into glucose-rich corn syrups. These are then transformed into fructose syrups by enzymes e.g. isomerase, and then refined. The fructose syrups are blended with the glucose syrups to make variety of commercial syrups.

In contrast, while the extraction of sugar from sugar cane has many steps, it doesn’t need the enzyme work. The cane is shredded and rolled to extract the sweet sap. This then goes through a series of boiling and evaporation steps to drive off water and concentrate the syrup. Plus there’s filtering, centrifuging, removal of impurities with lime and finally recrystallization to obtain the sugar crystals we know.

7. Not a problem in Australia

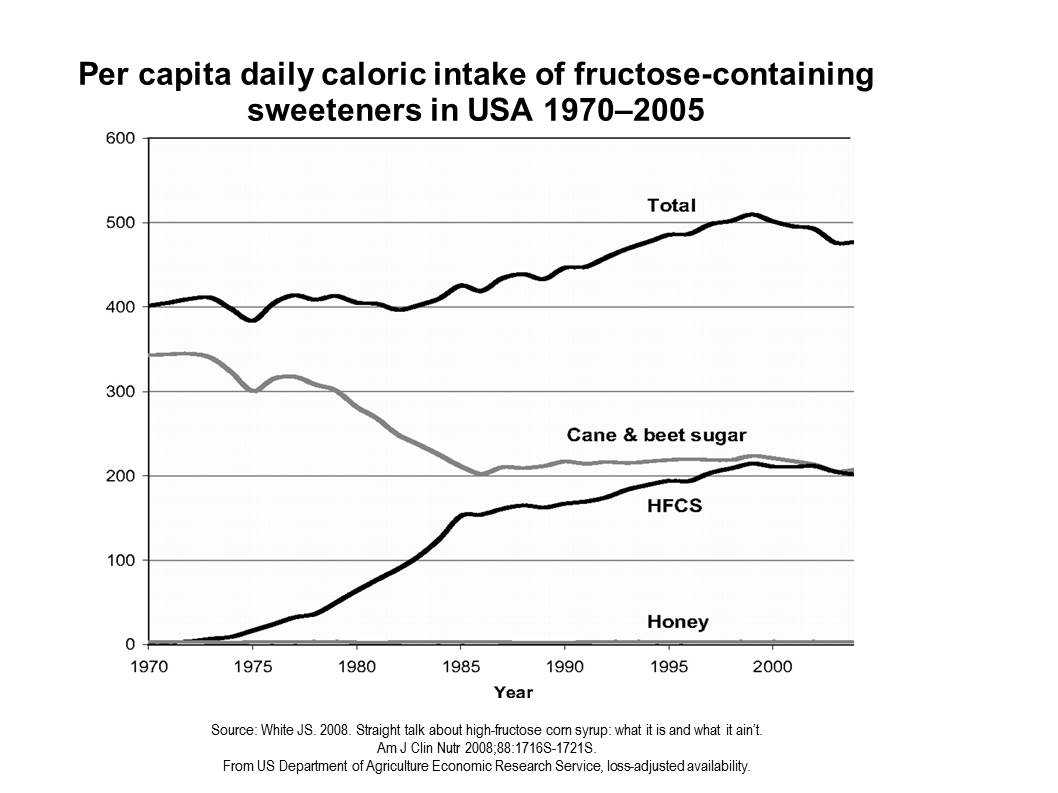

Starting in the 1970s, HFCS replaced sugar in the US and other countries where they grow lots and lots of maize. In the US, high fructose corn syrup gradually replaced sucrose from cane sugar. This is because manufacturers needed a cheap, readily available alternative to sugar which was expensive and in short supply due to the US ban on imports from Cuba, which grew most of their sugar cane.

8. Is HFCS linked to obesity and Type 2 diabetes?

The shift from using sucrose to HFCS, in the US, was noticed by nutrition researchers who wondered if it was linked to the obesity epidemic. HFCS use had paralleled the rise in obesity and type 2 diabetes since the 1970s, leading Bray et al to suggest that the overconsumption of high fructose corn syrup in sweetened beverages was responsible.

Since then, other studies have failed to show such a relationship. Today, HFCS is considered in the same light as cane sugar – something that contributes sugar and calories and should be kept to a minimum.

HFCS is not widely used in foods in Australia and New Zealand, which mainly use cane sugar, but you may see it occasionally in imported products.

9. There are three types of HFCS

High fructose corn syrup is not a single product. It consists of a group of three different liquid sweeteners that all come from maize or corn. The most widely used one is HFCS-55, which is used to sweeten drinks.

The two main types are:

1. HFCS-55

This is mostly used in beverages like soft drinks, fruit drinks, energy drinks and cordials. It contains on average 55 per cent fructose with the rest being 45 per cent glucose plus a smattering of glucose double units such as maltose and glucose triple units. The higher the fructose, the sweeter the syrup, so this one is preferred by the soft drink companies. Currently it’s used in 93 per cent of soft drinks in the US, where it’s cheaper than sugar.

2. HFCS-42

This is used in many baked goods, canned fruits and dairy products. It contains on average 42 per cent fructose and 58 per cent glucose.

Plus

3. HFCS-90

In addition, small quantities of HFCS 90 (90 per cent fructose) are also produced for ‘specialty applications’ such as canned fruits, confectionery and dessert syrups, and for re-blending with lower fructose syrups.

10. HFCS is more akin to sugar

HFCS is a sugar syrup, close to honey and invert sugar in its ratio of fructose to glucose. Sucrose, which is extracted from sugar cane or sugar beets, is a mix of the same two simple sugar molecules, being 50 per cent fructose and 50 per cent glucose. But these monosaccharides are linked together through a chemical bond in the disaccharide sucrose whereas in HFCS, they are free and unbound which I believe makes a difference. The body has to work to break the bond in sucrose during digestion whereas it can skip this step with HFCS as the molecules are free and ready for absorption and utilization.

| Component |

HFCS-55 |

Sucrose | Fructose |

Corn Syrup | Invert Sugar |

Honey |

| Fructose % | 55 | 50 | 100 | 0 | 45 | 49 |

| Glucose % | 42 | 50 | 0 | 100 | 45 | 46 |

| Others % | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 5 |

Simplified from White JS 2008 AJCN Am J Clin Nutr December 2008 vol. 88 no. 6 1716S-1721S.

Please note: These figures are from a US research paper and the sugars in syrups vary from country to country and from region to region as they are extracted from natural sources.

Bottom line

HFCS-55 resembles honey or invert sugar. It is sweeter than sucrose and is probably digested quicker as it doesn’t have to be broken down. That said, HFCS does contribute to added sugars and kilojoules/Calories for no nutritional value and will contribute to weight gain, if taken in excess.

What we need is LESS sugar, of any kind in our diets, regardless of whether or not a specific type of sugar is more or less dangerous.

There’s little scientific evidence that HFCS actually has a harmful impact, above and beyond the harm sustained from over-consuming sweetened products. The higher sweetness of fructose at room temperature actually suggests, that the same taste can be achieved with less sugar, which – at least in a purely metabolic equation – would be healthier.

You may also be interested in...

The Good Stuff

The Boring Stuff

© 2024 Foodwatch Australia. All rights reserved

Author photo by Kate Williams

Website by Joomstore eCommerce